Scott Edwards & Tim Edmunds

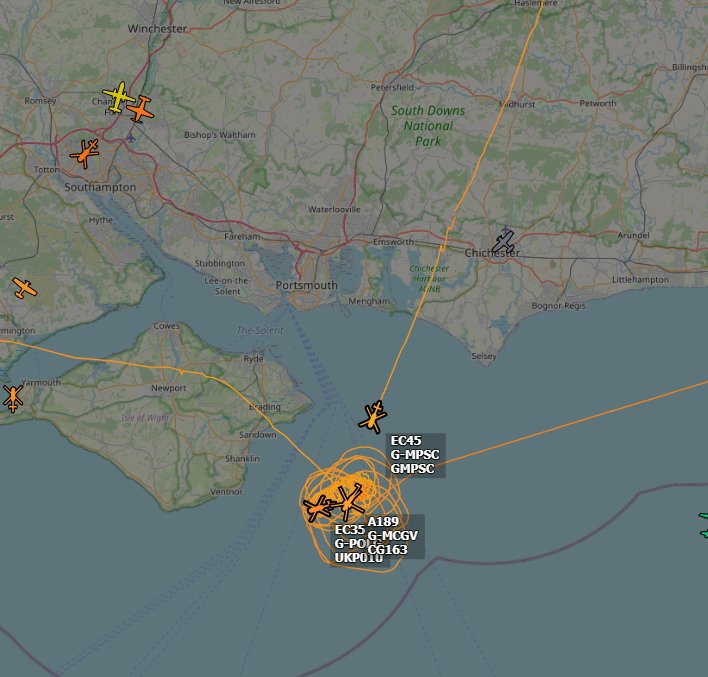

On October 25th at around 10am, just off the coast of the Isle of Wight, seven stowaways turned violent and threatened the crew of the Nave Andromeda, sparking concerns of a hijacking and intervention by the coastguard and police. A three-mile exclusion zone was put into effect around the ship for 10 hours, before the Navy’s Special Boat Service (SBS) boarded the ship and detained the stowaways.

Much of the reporting has revolved around the intervention of the SBS in this incident. But it should also encourage us to reflect more widely on the implications for UK maritime security.

Maritime security in home waters

What maritime security risks does the UK face in its own waters? In this case, the stowaways’ actions seemed to have resulted from their attempts to claim asylum in the UK being frustrated by the crew’s actions to detain them prior to the ship entering the Port of Southampton.

Initially however, the seizure sparked concerns about maritime terrorism, including potentially the use of the tanker to cause damage to UK ports or inflict an environmental catastrophe off the British coast. Fears centred on the ship containing significant quantities of oil that could in theory facilitate such an attack, though this was later dismissed.

Such concerns are indicative of a wider set of maritime security risks, challenges and demands in UK waters.

A potential terrorist incident at sea remains perhaps the foremost of these. In particular, the spectre of a mass casualty ‘Mumbai style’ attack on a ferry or cruise liner looms large in the worst-case scenarios of UK maritime security planners.

Other risks include criminal or state-based threats to submarine cables and other maritime infrastructures, smuggling and trafficking of various sorts, as well as demands to protect and police fishing grounds and Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), the maintenance of public order at sea – for example in the event of clashes between rival fishing boats, the blockade of a port – and the need to ensure maritime safety and to protect lives at sea.

Preparedness

To what extent is the UK prepared for such challenges? On this occasion the crew quickly secured themselves in the ship’s citadel, an action which was followed by a swift, well-coordinated and effective maritime security response. This involved multiple agencies including the police, coastguard and Navy, and culminated in an SBS boarding action which was able to take control of the ship quickly and bloodlessly.

But was the UK also lucky in this case? The stowaways appear to have been relatively compliant beyond the initial reports of violence. The incident took place close to shore and in Channel waters, where response times are short and key assets close to hand. The SBS has its headquarters at Poole – only a few miles from the site of the hijacking. Hampshire police is one of the best equipped and most active maritime forces in the country. Maritime domain awareness, surveillance and coordination capacities are at their strongest off the south coast.

Not all the UK’s maritime spaces are so well served.

Beyond seablindess

These events highlight the importance of the UK’s maritime spaces, and the challenges that these can present for security policy and practice.

In Britain, we have become accustomed to thinking of the seas off our coasts as safe and well-ordered spaces for commerce, transportation and leisure. For the most part, and at most times, this remains the case.

Yet the Nave Andromeda incident is not the only one in recent months that suggests this benign picture may be partial at best. The increase in asylum seekers risking their lives to cross to the UK in small boats has highlighted challenges of maritime border management, search and rescue and people smuggling by sea. Major drug seizures in ports highlight the importance of maritime routes to drug traffickers. And Brexit is likely to place new demands on the UK to police and manage its fishing grounds and other maritime resources.

Different maritime risks can be linked – or have the potential to escalate – in ways that are not always easy to appreciate or predict. In this case the problem of stowaways on board became a more serious challenge and, initially at least – raised concerns over of a potential terrorist threat. It is plausible that similar chains of events might end less happily in future.

Migration and security

Maritime security cannot be considered in isolation from other policy areas. The Nave Andromeda case, similar to the rise in small boats crossing the Channel, proved fundamentally to be a problem of migration, human tragedy and desperation, as much as it was one of maritime security.

These are issues that cannot be addressed by maritime security responses alone. As we have argued elsewhere in the context of the small boats crisis, migration issues are ultimately best served by migration policy.

In the case of the UK, the restriction of legal migration options such as the refugee resettlement scheme and obstacles in more traditional migration routes due to COVID-19 controls, have encouraged desperate asylum seekers to opt for risky maritime crossings in order to reach the UK.

Any long-term solution to these challenges must be found in an effective and humane migration policy rather than in policing the consequences of its absence.

Building capacity

None of this means that the UK can ignore the demands of maritime security. Outside of the Channel and certain other areas of strategic priority – such as coastal nuclear power stations or military installations – maritime security capacities are more fragmented and inconsistent.

If it had taken place elsewhere, the Nave Andromeda incident may have proved more difficult to manage.

Certainly, stowaways pose problems for ports beyond the Channel too, and this also applies to other potential maritime risks too, including those with far graver potential consequences than a last ditch bid for asylum by desperate migrants.

Either way, the UK cannot afford to be ‘seablind’ in its own waters. There needs to be a proper recognition of maritime security in future policy and resourcing decisions, including in the government’s ongoing Integrated Review.

Importantly, such efforts must include not only the Navy and marines, but other key maritime security and governance agencies too. These include the police, coastguard, Border Force and Marine Management Organisations, as well as the mechanisms and processes through which these organisations train and coordinate with each other.

Future responses

The Nave Andromeda incident demonstrated how the UK can respond effectively to a maritime security crisis when it occurs. But this should not stop the government from reflecting hard on the implications of this this case for maritime security more widely and ensuring that responses to potentially more serious incidents in future are just as successful.

For a PDF of this commentary, click here

This article originally put the time of the incident mistakenly as 10pm, rather than 10am, and has been amended